(first-notebook)=

# Your first notebook

**(10 minutes)**

Select the Python 3 icon. The Launcher tab will be replaced with a new Python notebook.

You'll see your first empty

cell, labeled `In [1]`.

If you look at the notebook's tab near the top of the page, you'll see that the

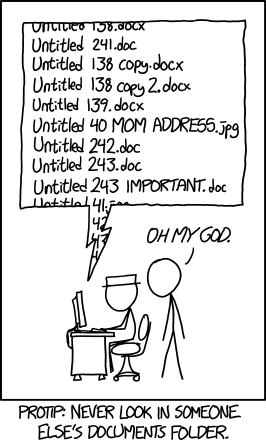

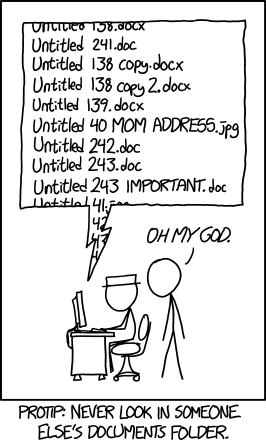

name of the notebook is {guilabel}`Untitled`. The first thing you should do when

creating a new notebook is to give it a new name. Go to Jupyter's

{guilabel}`File` menu and select {guilabel}`Rename Notebook...` (near the middle of the menu). Pick any

name you wish, such as `pythontest`.[^untitled]

[^untitled]: You don’t *have* to do this. But if you don’t, your home directory will soon be littered with notebooks named Untitled.ipynb, Untitled1.ipynb, Untitled2.ipynb, etc., and you won’t know what’s in any of them.

:::{figure-md} documents-fig

:class: align-center

by Randall Munroe

:::

After you've renamed the notebook, look at your directory listing on the left.

You'll see the notebook file with the extension `.ipynb`.[^f50]

[^f50]: Here are more [Jupyter

hints](https://www.dataquest.io/blog/jupyter-notebook-tips-tricks-shortcuts/).

Of particular interest is the list of [keyboard

shortcuts](https://coderefinery.github.io/jupyter/interface/#keyboard-shortcuts);

for some reason, you can't see the list they mention

in more advanced versions of JupyterLab, though the shortcuts are still there.

Some of those tips won't work on the Nevis systems; e.g., you can't

install new extensions on the Nevis notebook server. The last tip, on

different ways to share notebooks, will be helpful to those who work

with folks who don't use Jupyter.

Copy-and-paste the following into that first cell.[^f51]

[^f51]: You can type it in manually if you want, but (a) that's a lot of

typing, and (b) you have to make sure you get each character correct

for the sake of this example.

:::{code-block} python

from ROOT import TH1D, TCanvas

my_canvas = TCanvas("mycanvas","canvas title",800,600)

example = TH1D("example","example histogram",100,-3,3)

example.FillRandom("gaus",10000)

exomple.Draw("E")

my_canvas.Draw()

:::

:::{note}

This code is in Python, but after going through {ref}`the basics`

you can probably figure out what most of these lines are

supposed to do.

:::

To "execute" the contents of a given cell, hit SHIFT-ENTER with your

cursor in that cell. Do that now.

Oops! There's an error. Fix the error in the cell and hit SHIFT-ENTER

again.

:::{note}

Assuming there have been no mistakes, you should see a histogram

embedded in the web page.

There are also a couple of warning messages:

Warning in : Deleting canvas with same name: mycanvas

Warning in : Replacing existing TH1: example (Potential memory leak).

Let's think about what those messages mean. When you execute lines in a

cell, your environment doesn't "start fresh"; everything you defined

before is still there. ROOT is warning you that the `TCanvas` and the

histogram are being overridden.

In Python, you can usually ignore these warnings.

:::

Click in the next cell and copy-and-paste this line, then hit

SHIFT-ENTER:

exampleFit = example.Fit("gaus")

:::{note}

This next cell recognizes the histogram object you defined in

the previous cell. This gives you some idea of one feature of notebooks:

You can fiddle with something in a given cell until it does what you

want, then move on to the next phase of your task that depends on the

previous cell.

Wait a moment... We just added a fit to the histogram, but the plot

didn't change. Maybe we have to plot it again.

:::

Enter this line after the one you just pasted, or into a subsequent

cell, and hit SHIFT-ENTER:

example.Draw()

:::{note}

No new plot, and the plot above it still didn't change. What's wrong?

Nothing. Jupyter runs in a web browser, and browsers behave differently

than X-Windows (the underlying graphics protocol of UNIX). You may have

noticed that, unlike the ROOT plots in {ref}`the basics`, the shape of the cursor

doesn't change as you move it over the plot, and right-clicking on it

brings up a browser menu, not a ROOT one. If you right-click on the plot

and select {guilabel}`View Image`, you'll see that the plot is not a dynamic

object, but a static `.png` file.[^f52]

:::

[^f52]: "PNG" stands for Portable Network Graphics. It's a standardized

format for uncompressed images to be sent over the web. Jupyter uses

that format instead of GIF because the GIF algorithm is patented.

How do we get a plot? You probably guessed the answer from what I had in

the first cell. Paste the following line after that last `Draw()`

command, or in a new cell:

my_canvas.Draw()

Finally, you see the histogram with the fit superimposed.

:::{note}

{ref}`Remember `: ROOT

plots everything in a canvas. In Jupyter, a `TCanvas` is not automatically

drawn when its underlying plot updates. You have to explicitly draw the

`TCanvas` yourself. That's why the first example contains the lines:

my_canvas = TCanvas("mycanvas","canvas title",800,600)

# ... stuff ...

my_canvas.Draw()

I had to define the `TCanvas` that would be used as the "target" of any

Draw commands, then Draw that `TCanvas` in order for the plot to be

displayed.[^canvases]

:::

[^canvases]: Since we haven't had to explicitly define our canvases before, I

should mention: the canvas name and title are usually not important;

the name only matters if you were to write the canvas to a file, and

the canvas title is rarely displayed (as opposed to the histogram

title, which appears at the top of the plot).

What matters is the size of the canvas. Here, I used 800 pixels wide

and 600 pixels tall, which is the size of our old friend `c1`

that's automatically defined if you don't define a canvas yourself.

I could have defined the canvas using only defaults with

my_canvas = TCanvas()

but I thought that might be even more confusing to see for the first

time.

by Randall Munroe

:::

After you've renamed the notebook, look at your directory listing on the left.

You'll see the notebook file with the extension `.ipynb`.[^f50]

[^f50]: Here are more [Jupyter

hints](https://www.dataquest.io/blog/jupyter-notebook-tips-tricks-shortcuts/).

Of particular interest is the list of [keyboard

shortcuts](https://coderefinery.github.io/jupyter/interface/#keyboard-shortcuts);

for some reason, you can't see the list they mention

in more advanced versions of JupyterLab, though the shortcuts are still there.

Some of those tips won't work on the Nevis systems; e.g., you can't

install new extensions on the Nevis notebook server. The last tip, on

different ways to share notebooks, will be helpful to those who work

with folks who don't use Jupyter.

Copy-and-paste the following into that first cell.[^f51]

[^f51]: You can type it in manually if you want, but (a) that's a lot of

typing, and (b) you have to make sure you get each character correct

for the sake of this example.

:::{code-block} python

from ROOT import TH1D, TCanvas

my_canvas = TCanvas("mycanvas","canvas title",800,600)

example = TH1D("example","example histogram",100,-3,3)

example.FillRandom("gaus",10000)

exomple.Draw("E")

my_canvas.Draw()

:::

:::{note}

This code is in Python, but after going through {ref}`the basics`

you can probably figure out what most of these lines are

supposed to do.

:::

To "execute" the contents of a given cell, hit SHIFT-ENTER with your

cursor in that cell. Do that now.

Oops! There's an error. Fix the error in the cell and hit SHIFT-ENTER

again.

:::{note}

Assuming there have been no mistakes, you should see a histogram

embedded in the web page.

There are also a couple of warning messages:

Warning in : Deleting canvas with same name: mycanvas

Warning in : Replacing existing TH1: example (Potential memory leak).

Let's think about what those messages mean. When you execute lines in a

cell, your environment doesn't "start fresh"; everything you defined

before is still there. ROOT is warning you that the `TCanvas` and the

histogram are being overridden.

In Python, you can usually ignore these warnings.

:::

Click in the next cell and copy-and-paste this line, then hit

SHIFT-ENTER:

exampleFit = example.Fit("gaus")

:::{note}

This next cell recognizes the histogram object you defined in

the previous cell. This gives you some idea of one feature of notebooks:

You can fiddle with something in a given cell until it does what you

want, then move on to the next phase of your task that depends on the

previous cell.

Wait a moment... We just added a fit to the histogram, but the plot

didn't change. Maybe we have to plot it again.

:::

Enter this line after the one you just pasted, or into a subsequent

cell, and hit SHIFT-ENTER:

example.Draw()

:::{note}

No new plot, and the plot above it still didn't change. What's wrong?

Nothing. Jupyter runs in a web browser, and browsers behave differently

than X-Windows (the underlying graphics protocol of UNIX). You may have

noticed that, unlike the ROOT plots in {ref}`the basics`, the shape of the cursor

doesn't change as you move it over the plot, and right-clicking on it

brings up a browser menu, not a ROOT one. If you right-click on the plot

and select {guilabel}`View Image`, you'll see that the plot is not a dynamic

object, but a static `.png` file.[^f52]

:::

[^f52]: "PNG" stands for Portable Network Graphics. It's a standardized

format for uncompressed images to be sent over the web. Jupyter uses

that format instead of GIF because the GIF algorithm is patented.

How do we get a plot? You probably guessed the answer from what I had in

the first cell. Paste the following line after that last `Draw()`

command, or in a new cell:

my_canvas.Draw()

Finally, you see the histogram with the fit superimposed.

:::{note}

{ref}`Remember `: ROOT

plots everything in a canvas. In Jupyter, a `TCanvas` is not automatically

drawn when its underlying plot updates. You have to explicitly draw the

`TCanvas` yourself. That's why the first example contains the lines:

my_canvas = TCanvas("mycanvas","canvas title",800,600)

# ... stuff ...

my_canvas.Draw()

I had to define the `TCanvas` that would be used as the "target" of any

Draw commands, then Draw that `TCanvas` in order for the plot to be

displayed.[^canvases]

:::

[^canvases]: Since we haven't had to explicitly define our canvases before, I

should mention: the canvas name and title are usually not important;

the name only matters if you were to write the canvas to a file, and

the canvas title is rarely displayed (as opposed to the histogram

title, which appears at the top of the plot).

What matters is the size of the canvas. Here, I used 800 pixels wide

and 600 pixels tall, which is the size of our old friend `c1`

that's automatically defined if you don't define a canvas yourself.

I could have defined the canvas using only defaults with

my_canvas = TCanvas()

but I thought that might be even more confusing to see for the first

time.