Clearer Code

Here’s a repeat of the “faster code” from the previous section:

# Compute the vector product of the two velocities

i = 10

k = i + 3

m = i + 1

while j < m:

s[j] += k*j

j += 1

I’m going to start with an “iffy” style issue: From this code, we

can’t tell what the initial value of j is supposed to be.

Since j is presumably assigned outside this fragment from a larger

program, it may be that the calculation of j is complicated.

However, it may also be that the programmer stuck j=0 somewhere

near the top of the program. This leaves us, the code’s reviewers, in

doubt about the limits of the loop.

So I’ll only go as far as to claim:

Style problem 0.5: The initial loop limit may be defined too far from the start of the loop. In general, one would like the loop limits to be defined near the loop statement.

My next style complaint has to do with the single-letter variable names. A single letter may be appropriate for the loop index,1 but for the other variables a single letter just hides what’s going on.

Style problem 1: The variable names tell us nothing about what the variables do.

Style problem 2: The comment has nothing to do with the code.

Comments

I’m about to go off the deep end. What follows is very subjective. But if you’re willing to wade through it, you might come out writing better programs.

Program comments are my pet peeve. In my view, the comments are part of the code. When you write the code, write the comments. When you revise the code, you revise the comments.2

The comment says “Compute the vector product of the two velocities” but the code has nothing to do with vector products. When you see something like this, it means that someone revised the code, but left the comment unchanged.

This is just as bad as having no comments at all, if not worse. Anyone else looking at the code is going to be confused, since the comment says one thing and the code says another.

Writing comments can be tedious. But revising uncommented or badly-commented code is a nightmare.

One more time:

Put comments in your code.

Describe the purpose of the section of code. You don’t have to describe the syntax of each line (unless it uses an obscure feature of the language); there are plenty of web sites on programming-language syntax.

The comments are part of the code. When you revise the code, revise the comments.3\(^{,}\)4

With all that said, let’s take a look at what the revised code might look like:

# For each user, add a displacement to the distance array

interval = 10

scale = interval + 3

limit = interval + 1

j = 0 # or previously calculated elsewhere

while j < limit:

distance[j] += scale*j

j += 1

We’re faster and clearer than when we started. In the next section, we’ll see if we can use the programming language make things even faster for us.

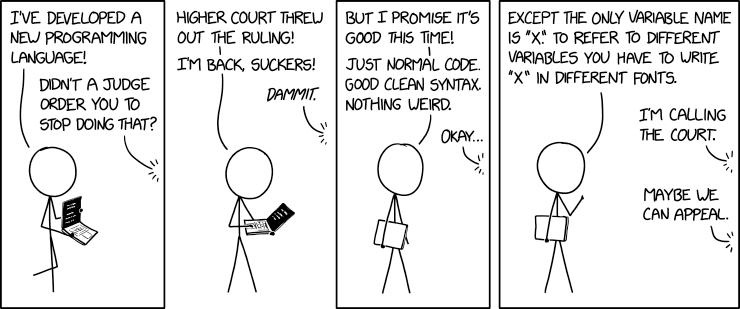

Figure 106: https://xkcd.com/2309/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

Back in the good ol’ days, scientists programmed in FORTRAN. As the name implies (FORTRAN = “FORmula TRANslation”), the language was designed to implement mathematical expressions as directly as possible, given the punch-card technology of the time. Back then, FORTRAN variable names could not be more than six letters long (yes, really!), and mathematical notation mainly uses single letters for indexing matrices and such.

That’s why, to this day, there is a tendency to use

i,j,k, etc. as the loop variables in programs, along with simple repeats likeii,jjj,k3.- 2

I know there’s a strong impulse to get to it “later.” As I said before, as of 2025, the ATLAS collaboration collected over 180 fb\(^{-1}\) of data, and they still haven’t discovered experimental evidence of “later”! I’m an experimentalist, not a theorist, which is why I put comments in my code.

- 3

Remember when they made you take an English class in college, even though you’re a science major? I imagine you thought that this was to teach you to think critically, to better enjoy literature, to understand the world with nuance and conviction, to appreciate differences, to develop sensitivity, and to contribute to the future of culture.

Well, yeah, I suppose so. But the real reason was to teach you how to write and revise program comments.

- 4

Occasionally you will meet people who claim that there’s no need to comment their code, because their choice of variable names is so good that the code is “self-documenting.” There are also people who claim to have seen Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster. I lump all those claims into the same category.

To put it another way: The goal of writing comments is to document the code’s purpose and to save time for the next person who has to work with it. If you’re forcing the next person to analyze your variable names and deduce the code’s function, you haven’t saved anyone any time.