Pointers: A too-short explanation (for those who don’t know C++ or C)

(5 minutes)

On the previous page we used the pointer symbol “->” (a dash followed

by a greater-than sign) instead of the period “.” to issue the

commands to the TTree. This is because the variable tree1 isn’t

really the TTree itself; it’s a “pointer” to the TTree.

The detailed difference between an object and a pointer in

[] TH1D hist1("h1","a histogram",100,-3,3)

This creates a new histogram in ROOT, and the name of the histogram

“object” is hist1. I must use a period to issue commands to the

histogram:

[] hist1.Draw()

Here’s the same thing, but using a pointer instead:

[] TH1D *hist1 = new TH1D("h1","a histogram",100,-3,3)

Note the use of the asterisk “*” when I define the variable, and the

use of the new. In this example, hist1 is not a

‘object,’ it’s a ‘pointer’ to the location in computer memory where the

object hist1 is stored. I must use the pointer syntax to issue

commands:

[] hist1->Draw()

Take another look at the file c1.C that you created in a previous

example. ROOT uses pointers for almost all the code it creates. As I mentioned previously, ROOT

automatically creates variables when it opens files in interactive mode;

these variables are always pointers.

It’s a little harder to think in terms of pointers than in terms of

objects. But you have to use pointers if you want to use the

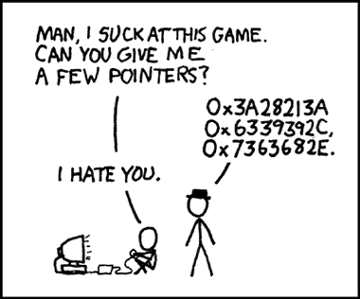

Figure 61: https://xkcd.com/138/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

Believe me, if there were a way to teach ROOT/

C++ without using pointers, I’d do it. I know the concept is an additional barrier to understandingC++ for those who’ve only been exposed to Python.You also have to use pointers to take advantage of object inheritance and polymorphism in

C++ . ROOT relies heavily on object inheritance (some would say too heavily), and this is often reflected in the code it generates.At this stage, I’ll suggest something that, as a scientist, you’re naturally reluctant to do: Take my word for it. Once you fully understand the object/pointer distinction and what pointers can be used for, you’ll appreciate the memory management that pointers offer. The automated memory management of languages like Python and Java superficially makes it easier to write code, but imposes limitations for advanced programming techniques.