Starting with Jupyter

(5 minutes)

In any web browser (laptop, desktop, tablet), go to

https://notebook.nevis.columbia.edu.1 You’ll be prompted for your

Nevis account name (just the name, no @<server-name>) and

password.2

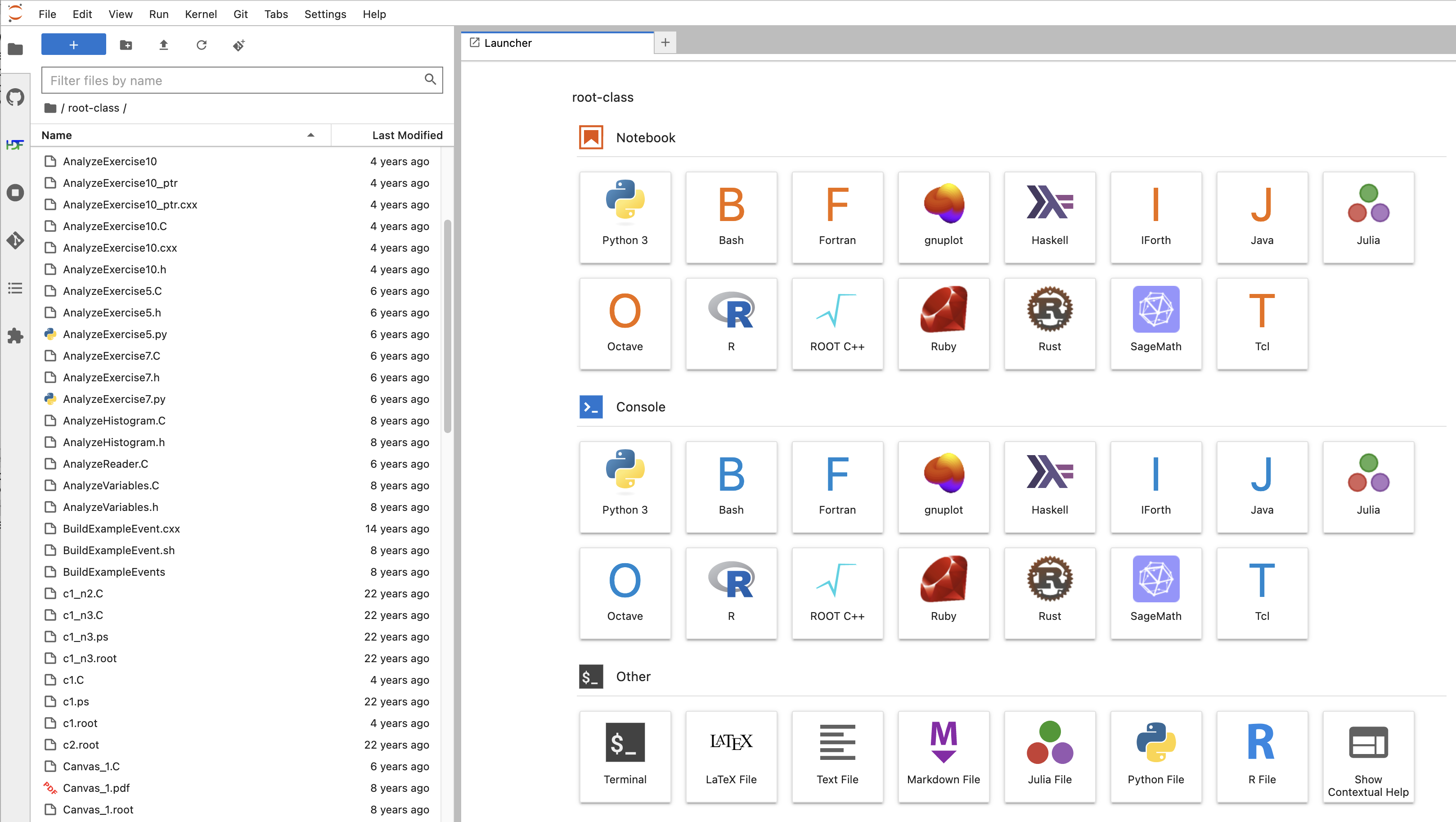

After the you login, there’ll be a pause while Jupyter starts up. Eventually you’ll see a display that looks something like this:

Figure 21: It won’t look exactly like this, for a number of trivial reasons.3

You are looking at JupyterLab, an browser-based method of running programs.

You’ll see your home directory in the left-hand panel. Look at Jupyter’s File menu, and also right-click on one of the filenames in the left-hand panel. This will give you an idea of the elementary file operations you can do directly from Jupyter.

The fun part is the area on the right with all the icons. This is the Launcher. It’s going to “disappear” when get to the next page of this tutorial; if you want to see it again, just click on the + symbol you can see in the top area of the window.

While there’s a lot to see in the Launcher, there are only three icons that will be relevant to this tutorial:

Figure 22: These are the only icons you have to pay attention to for this tutorial. In fact, the Terminal icon at the bottom isn’t all that important either, which is why I’ve circled it in a lighter shade.

For extra added Jupyter goodness, mouse over the icons you’ll see on the top left, to see the hovertext about what they do.

Figure 23: I’ve circled the auxiliary icons that I think might be potentially relevant to this tutorial or the work you’ll do this summer. As your familiarity with Jupyter increases, you’ll find use for the other icons.

Jupyter is intended to provide an IDE (Integrated Development Environment) in a web browser.4 Each one of the Notebook icons is a “kernel,” that is, an environment for interpreting commands. We’ll take a look at one of these kernels in the next section.5

Figure 24: https://xkcd.com/1202/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

Take care: it’s “https”, not just “http”.

- 2

If you don’t have an active account on the Nevis particle-physics cluster, then you won’t be able to login. You’ll have to install Jupyter on your own system or proceed without it; go on to Decisions.

- 3

What are those reasons?

The placement of the icons will depend on the size of your screen.

When I made this screenshot, I was visiting my

root-classdirectory. You probably haven’t copied over all those files.If you’re not using the Nevis notebook server, you almost certainly won’t see nearly as many icons. I’ve installed as many different languages and environments as I could.

Would any of those additional languages be of any use to you? If I’m honest, I was just showing off; I installed most of them just to show that I could.

If you’re curious:

While Julia might be useful in physics work, I know of no one at Nevis who uses it.

If you’re used to Matlab or Mathematica, you might want to take a look at the free equivalents Octave or SageMath respectively, which you can see are available on our notebook server.

If you want to explore some alternatives to programming in procedural languages (e.g., C++ and Python), you might want to look at Haskell and Forth. They are completely different from each other and from the languages you’re used to.

Here’s a complete list of all the Nevis notebook languages and environments.

- 4

Jupyter can’t do visual programming, that is, creating programs by moving icons around to form diagrams. Or rather, it can’t do that yet; Jupyter is under continual refinement. Who knows what we’ll be able to do next year?

- 5

The icons in the Console and the Other sections are for more advanced work with the notebook kernels. They’re not relevant for this tutorial, but you may want to read more about them if you use Jupyter notebooks for serious programming and debugging.