Resource Planning

If you’ve made it this far, then:

Congratulations!

You now know how to submit a condor job with very simple input/output requirements.

Your head must be spinning with all these files:

.cmdfiles,.shfiles,.pyfiles, etc.

There’s a reason for the nested scripts. It has to do with resource planning: Telling condor what inputs are needed to run your program, and how to handle any outputs.

Physicists hate resource planning.1 But if you’re going to use condor for any real task, you’ll have to do it.

Understanding the execution environment

Let’s take a look at some lines from condor-example.cmd, with a couple of modifications for the sake of discussion:

executable = condor-example.sh

transfer_input_files = condor-example.py

input = experiment.root

transfer_output_files = condor-example-$(Process).root

output = condor-example-test-$(Process).out

error = condor-example-test-$(Process).err

log = condor-example-test-$(Process).log

The purpose of these lines is to instruct condor which files have to be transferred to the batch node for your program to work, and which files should be copied back to you after your program is finished.2

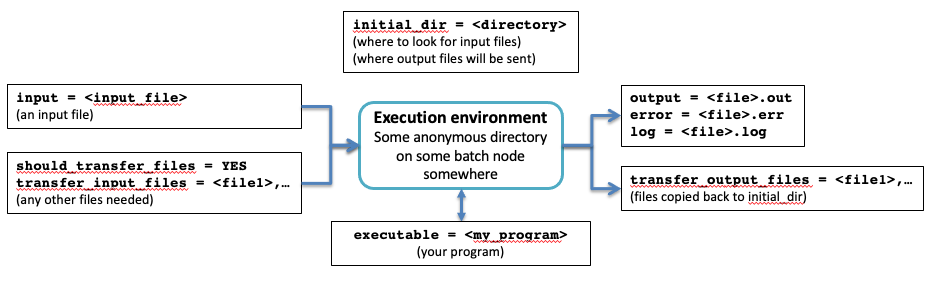

This diagram illustrates what’s going on:

Figure 120: The relationship between the lines in a .cmd file and the condor execution environment.

Note that output refers to the direct text output of your job

(such as print statements in python or cout statements in

C++). The error file will contain any error messages. The log file

will include some condor status messages, including the name of the

batch node on which your job executed.3

You can learn more about these statements in the HTCondor manual.

Stay within the execution environment

You’re not in Kansas anymore

Or to be less flippant, you’re not in your home directory anymore. When your job is executing on a batch node, your program (and any shell script that runs it) doesn’t have access to the files and environments that you might have set up in your home directory.

Take another look at condor-example.sh. The first few non-comment lines set up the execution environment for the Nevis particle-physics systems.4

If you’re not at Nevis, of course, you’ll have learn what form of preamble or set-up is required for your institution’s batch farm to replicate your environment.

In general, it’s not a good idea if your shell script (the .sh file)

references any directory outside the execution environment for that

particular process. The reason is that you may not know which batch

nodes will run your job, or if they have access to any external

directories.

You can fiddle with directories in condor, but you’ll want to keep it within the condor environment; e.g.:

# Create a new sub-directory within the condor execution environment.

mkdir myDirectory

# Visit this directory.

cd myDirectory

# Do something in that directory.

echo "This is a temporary file" > file.txt

# Leave the directory

cd ..

# Run something that uses that directory.

./myprogram.py --inputfile=myDirectory/file.txt

Test to see if everything works

This may sound trivial, but you’d be surprised at how often I see people skip this step: Test your condor job submission with 2-3 jobs before submitting a huge quantity like 20,000.

The reason why I’m giving this advice is that I’ve seen what happens when someone doesn’t do it, and there’s a problem with their job:

When a condor job fails, it sends an error message.

20,000 failed jobs means 20,000 error messages.

Sending out 20,000 error messages at once will clog our mail server, slowing it down. This does not make one popular.

The 20,000 error messages are sent to your email address at your home institution. Your home institution becomes suspicious, and shuts down your email address.

The

nevis.columbia.edumail server is identified as a potential source of spam, since it sent out 20,000 emails to a single address. Our mail server is added to spam block lists. Members of the Nevis faculty discover that their emails never arrive, and without any warnings. Again, this does not make one popular.

All of the above have happened, though fortunately not all at once. Still, to maintain your popularity, test your scripts first!

Find reasonable execution times for your jobs

The “sweet spot” for the length of a job is about 20-60 minutes.

Shorter than 5 minutes, and the overhead involved in condor setting up the execution environment and copying your files begins to take up a substantial percentage of the job’s execution time.

Longer than that, and your job may run up against condor’s time limit for a job. That limit is assigned by a systems administrator; for the Nevis particle-physics systems I’ve left this limit at its default of two hours.

That’s not a “hard” limit; if no other jobs are waiting to be executed, condor will let a job run over two hours. However, as soon as any other job requests to be executed, condor will “suspend” a job that’s taking too long. A suspended job has to start again from the beginning.5

A practical way to discover how long your job takes to run is to do some test submissions with varying values of an appropriate parameter; e.g., the number of events read from an input file, or the number of events to generate in a simulation.

Too many inputs

As you work with more elaborate projects, you may discover that you

need a longer and longer list of files to transfer with the

transfer_input_files option in the .cmd file.

There are two ways to deal with this. One way is to let

transfer_input_files copy an entire directory for you. For example:

transfer_input_files=myprogram.py,my_directory

If you have to transfer a lot of input files, put them in that directory. Then you reference that directory within your condor environment; e.g.:

./myprogram.py --inputfile=my_directory/experiment.root

It’s easy to get sloppy and forget about the contents of any such special directories. They tend to pick up “junk” that your condor job never uses, but transfers anyway because condor can’t tell the difference.

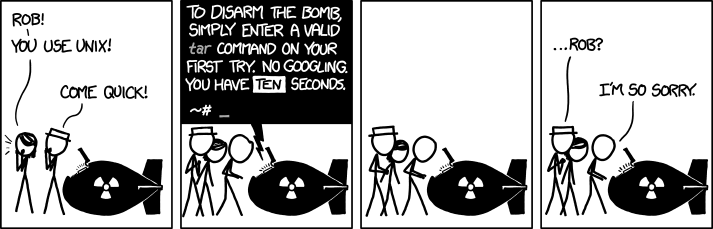

Therefore, I like to use the tar command to create an archive file that I will unpack in my condor job.6

Here’s an example from work that I’m doing right now (May-2022). I’ve got a program that I want to submit to condor. I developed the program and its associated files as I worked in a directory. That directory is filled with all kinds of temporary files, test scripts, and other junk:

> ls work-directory

10000events.mac example.hepmc2 grams.gdml LArHits.h root

atestfil.fit example.hepmc3 gramssky mac scripts

bin example.treeroot GramsSky Makefile test

btestfil.fit GDMLSchema gramssky.hepmc3 options.xml test.mac

c1.gif gdmlsearch grams-z20.gdml options.xml~ test.root

c1.pdf gdmlsearch.cc~ hepmc3.mac outputs-pretrajectory treeViewer.C

CMakeCache.txt gramsdetsim hepmc3.mac~ output.txt user.properties

CMakeFiles GramsDetSim hepmc-ntuple.root parsed.gdml view.mac

cmake_install.cmake gramsdetsim.root HepRApp.jar radialdistance.root xinclude.xml

crab-45.mac gramsg4 heprep.mac rd.pdf

crab.mac GramsG4 HitRestructure.root README.md

detector-outline.mac gramsg4.root LArHits.C RestructuredEdx.root

I copy the work directory:

> cp -arv work-directory job-directory

Then I clean up job-directory to only contain the files I’ll need to run my condor job. Here it is after I’m done.

> ls job-directory

bin GDMLSchema gramsdetsim gramsg4 grams.gdml gramssky mac options.xml

For me, this is a “reference directory” for the jobs I’m going to submit. I can continue to fiddle with things in work-directory, but I’ll leave job-directory pristine until there’s a reason to change it.

This directory still contains a lot of files:7

# Count the number of files in job-directory

# and all its sub-directories.

> find job-directory -type f | wc -l

60

So it’s easier for me to transfer all these files as a single archive. I’ll create an archive of that directory:

> tar -cvf jobDir.tar ./job-directory

It’s the single jobDir.tar file that I’ll transfer and unpack in my

condor job. In my .cmd file, I’ll have:

transfer_input_files=jobDir.tar

In my .sh file, I’ll have:

tar -xf jobDir.tar

Then within my condor execution environment, I’ll have access to all the files in job-directory. For example:

./job-directory/gramsky --rngseed=${process}

That last option to gramssky supplies a unique random-number seed

for my sky simulation… but that’s another story.

Figure 121: https://xkcd.com/1168/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

In this discussion, when I say “physicists hate resource planning,” it’s not exclusive. Other fields of study also hate resource planning. However, since I mostly hang out with physicists and not physicians or morticians, I’ll only speak for the folks I know.

- 2

You might initially think that if your program produces any outputs, condor should simply transfer everything back to you. In reality, an execution environment often contains a lot of “junk”; one classic example are conda work files. It’s generally better to explictly tell condor which output files are relevant to you.

Why I didn’t do this in condor-example.cmd? When I first created that file, selective transfer of output files was not available in condor. And now… well, perhaps I’ll get around to it in time for the next edition of this tutorial.

- 3

The

.logoutput from condor is a bit different than the.outand.erroutput. If you run your job more than once with identical values foroutput=anderror=(in this example it would mean than you’re running the same with the same process number), the.outand.errfiles will be overwritten.However, the

.logis always appended to, not overwritten. If you see your.logfile gradually become larger and larger as you re-submit your jobs, it’s because the file is basically maintaining a “history” of every time you’ve run the job.- 4

Actually, on Nevis particle-physics systems, the directory

/usr/nevis/admis located outside the condor execution environment. This works on our batch farms because of the way directories are managed here.- 5

At one time we had someone try to submit a week-long spline calculation on a Nevis batch farm. It never executed, because any time someone submitted a different job to the farm, the spine job was suspended and had to start from the beginning.

- 6

Why don’t I use zip? Mostly it’s personal preference: although

taris a bit harder to use, it’s more powerful thanzip. Also,zipisn’t always part of a standard Linux installation, though I make sure it’s available on all the Nevis particle-physics systems.- 7

Mystified by the find? By the wc? And what’s the deal with that vertical bar?

Hey, I told you that you could spend a lifetime learning about UNIX!