Branching

Do you need to know this?

Git branching is described very well in the Git book. However, once again, I was asked to address this topic explicitly in this tutorial.

In the spirit of the previous page, I’m going to offer a perspective on using branches that I think would be the most relevant to your work in physics.

Don’t get confused

In ROOT, there are branches, in the sense of columns in a ROOT TTree. In git, there are branches, in the sense of alternative versions of your files.

It’s quite possible to use both meanings of the word in a single sentence: “You need to create a new branch in order to add a new branch to the n-tuple.”1

You’ll just have to smurf the meaning of the word through context.2

Let’s return to the condor-example.* example on the

previous page. You’re figuring out how to add a third

argument to condor-example.py and have

condor-example.sh invoke the program with that new argument.

As you’re doing that, you realize that as you add more arguments to

the program, the order of the arguments doesn’t make sense. You want

to add a brand-new feature to the program: parsing its arguments the

way the root-python-setup.* scripts do.

Rather than trying to do two changes at once, you decide to create a “branch” in your code development: you’ll restore the files to what they were before you started working on them, create a new branch, and work on this new feature there.

It might look something like this:

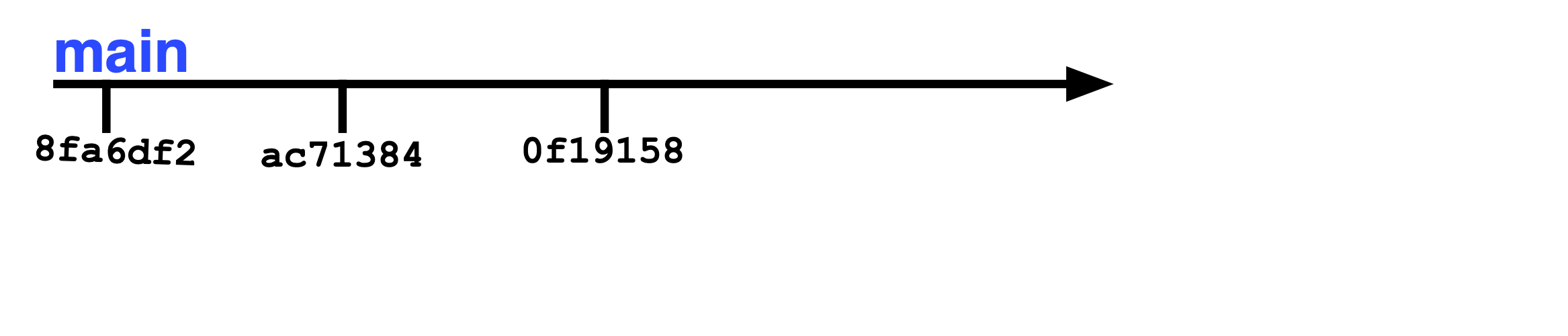

Figure 133: This is our starting point. We’ve worked on the main branch, making

commits as we go along. The example ID numbers might be what you’d see

if you used git reflog.

# Commit where you are right now, perhaps part-way through

# your current work.

git commit -a "in the middle of adding that third argument"

# You want to rewind to the point before you started to make

# changes. First, check the ID numbers of your previous commits.

git reflog

# You're comfortable rewinding to this particular previous commit

git checkout ac71384

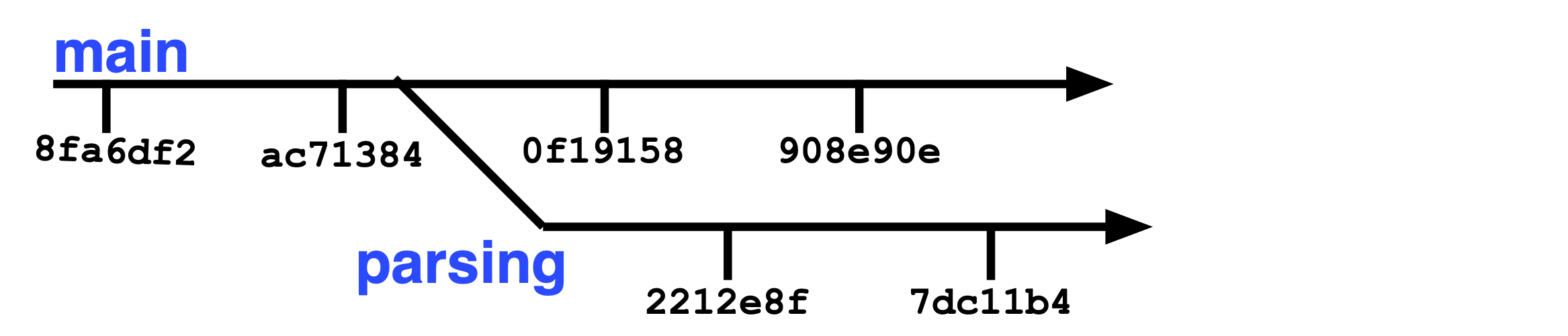

Figure 134: We’re going to create a brand-new branch in our code. I’ve arbitrarily called it “parsing”, because its purpose to add some kind of parsing to our code. On this new branch we can make new commits. We can also switch back to the main branch and commit completely separate changes if we wish. The two branches are separate.

# Create a brand-new branch from here. Anything you do in

# the 'parsing' branch won't affect what happens

# in your main code.

git branch parsing

# Switch to working on this new branch

git checkout parsing

# Start editing files in the 'parsing' branch. You

# can commit changes here; this will only affect

# files in that branch.

git commit -a -m "some change in the 'parsing' branch"

# At any time, you can switch back to the main work you

# were doing. If you recall, we named the main branch 'main'.

git checkout main

# Any work you do in 'main' is not reflected in the

# 'parsing' branch, and vice versa.

git commit -a -m "some changes made to 'main'"

git checkout parsing

# ... make changes here ...

git commit -a -m "more changes to the 'parsing' branch

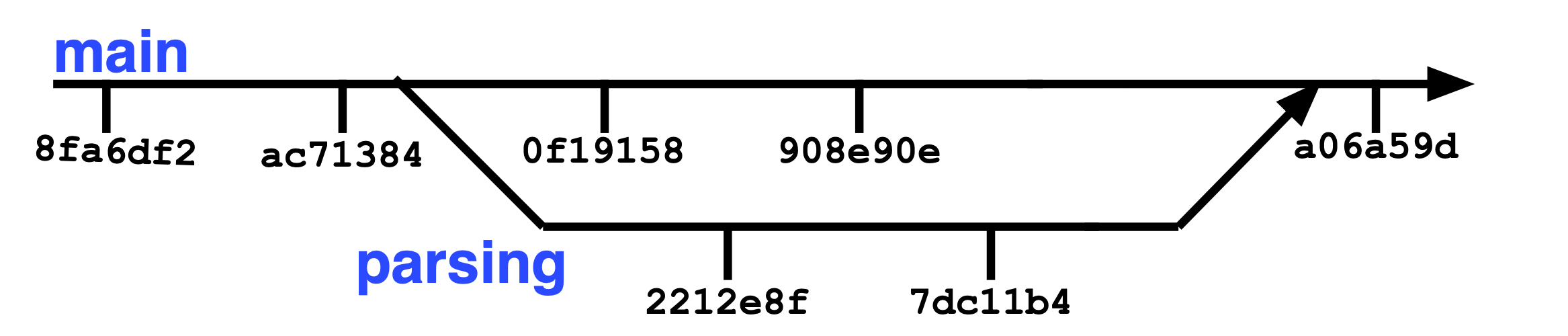

Figure 135: We’ve made all the changes we’d like to in the “parsing” branch. Now we decide to incorporate those changes into the main branch. We’ll merge the branches together. If there are some lines for which it’s not clear which should take precedence, git will let us know and we’ll have to choose.

# At some point, you may decide to merge the work you've

# done in the 'parsing' branch back into the 'main'

# branch.

git checkout main

git merge parsing

# This incorporates the changes you made in 'parsing'

# into 'main'.

In this simple example, it’s likely that you’ve edited the same files in both branches and will have to resolve some conflicts. Git will warn you about this, and ask that you inspect your files.

When you look in your files, you’ll see a bunch of lines that begin with

<<<<<<< and end with >>>>>>>, with the differences between the two

branches contained in-between. You’ll want to inspect those

differences and decide how you want to reconcile them.

Once you’ve fixed those differences, one final command will confirm the merge:

git commit -a

Confused?

I don’t blame you. I used a very small set of files and a very simple example to illustrate branching. From your perspective, I wouldn’t blame you if you thought the whole idea was useless.

What happens in real life is that you’re in the middle of a software project that involves a large number of files. Someone else wants to make a major change in your code. They can create a branch so that their work doesn’t interfere with yours.

Using branches means thay they can make and test their changes without affecting the rest of your work, even if their change involves the same files you’re editing. Their work and your work can remain separate, at least for a while, until the time comes to merge it.

I haven’t forgotten

I’m sure you still remember that I lied to you. I’m going to come clean in the next section.

Figure 136: https://xkcd.com/2956/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

Let’s hope you’re not asked to do this while you’re sitting on the freshly-grafted limb of a tree.

If you asked what if that tree was located in front of a recently-constructed extension building for the public library, then you and I shall get along well during your summer research.

- 2

I thought about whether I should include a 1980s pop-culture reference in a ROOT tutorial written in the 2020s. Then I remembered that I asked you to search for an obscure reference in Exercise 1: Detective work. If I can ask you to smurf for “surf”, I think I can ask you to surf for “smurf”.