Why Git

Intended audience

If you’re wondering why we need a version-control system in the work we do, this section tries to answer that. If you already know why, you can skip this page and go to the next one.

Saving a file

Let’s start with an example that’s almost too simple: Assume you’re working on a document using a text editor. Every once in a while you hit to preserve your work. 1\(^{,}\)2\(^{,}\)3

You can think of this as “progress-based” saving: You’re saving your progress as you go along so you don’t lose your changes.

What if you reach a point in your writing when you realize that you’ve made a mistake? Most editors have some form of command. However, that feature usually only works for your current editing session; if you quit and your editor and restart it, you lose the “undos”.

Saving versions of a file

So far, so good. Now let’s think about a different approach to saving your work: task-based saving.

Assume you’ve been working on a document to accomplish a certain task. What a “task” is up to you. All that matters is that it’s represents a step in your work on the file.

Here some random examples off the top of my head:

You’re writing an article, and you’ve added a new section, along with bibliographic references.

You’re working on

Analysis.Cfrom this tutorial, and you’ve modified the code to generate histograms. You’d like to “bookmark” this change, before you move on to the next step in your work: writing those histograms to a file.

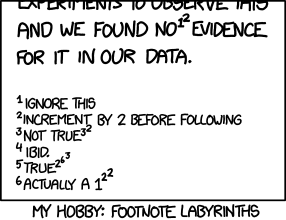

You wrote a ROOT tutorial, and you’re adding material on git, possibly with footnotes and xkcd cartoons.4

If we’re only talking about one file, a potential solution is to make a copy of the file at these signficant points, perhaps with a suffix to indicate why you made the bookmark; e.g.,

Analyze.C

Analyze-histograms.C

Analyze-write-histograms.C

Analyze-write-histograms-and-ntuple.C

Analyze-derive-pt.C

... and so on

This can become awkward5, but it works, at least for as long as you’re willing to come up with suffixes.

What if there were a way to have some program keep track of these “bookmarks” for you? With a way to track what changes you made, and perhaps a way to revert to an earlier version if you wished?

You’ve already guessed that this is what git can do for you.

Git management for one file

In the above example with Analyze.C, what what one might do instead is:6

# Once only: Set up the current directory to be managed by git

git init -b main

# Tell git to keep track of Analyze.C

git add Analyze.C

# Edit Analyze.C to do something different, then use a

# command like this. The option to '-m' is your comment

# on your change.

git commit Analyze.C -m "create histograms"

# Do some more work on Analyze.C, then commit those additional changes:

git commit Analyze.C

# Because I've omitted the '-m' option, git will prompt me with

# an editor session to add a comment. One reason to do this is that the

# comment can be several lines long.

# Make more changes to Analyze.C, then:

git commit Analyze.C -m "derive pt and include it in the ntuple"

Git management for many files

This might seem overkill for a single file. But in a real project, you might want to keep track of changes you made to many files in a coordinated way:

You might write a physics paper with each section in its own file, to make it easier for different people to review only those sections relevant to their work. These sections might have a shared bibliography file, so as each person adds additional references you (or they) would add lines to both their section and to the bibliography.

You’re working on analysis code that requires several programs to function. There’s an example of this in Friends: n-tuple columns in multiple files.

Another example comes from my own work: I have a program that requires a code file, a file of options to control its analysis logic, and a shell script to execute it.

To take another completely random example that comes to mind, suppose I’m adding a section on using git to a ROOT tutorial’s appendices. I’d have to change the file that defines the appendix table of contents, include a new file with the table of contens of the git sub-sections, and a file for each sub-section that explains an aspect of git (for example, a page like the one you’re reading now).7

This is where is a version-control system like git really shines: It can track all the changes to all the files you’ve told it to control.

Let’s set up a simplified example of using git to manage multiple files in a project. I’ll use the files from the Condor Tutorial in another one of the appendices.8

Let’s assume that you followed the directions on that page and have these files in a directory.

condor-example.cmd

condor-example.sh

condor-example.py

For the sake of simplicity let’s assume they’re the only files in that directory.

You could set up that directory to use git for version control:

git init -b main

Now we tell git which files in that directory we want to manage:

git add condor-example.py

git add condor-example.sh

git add condor-example.cmd

Note that we can get use UNIX’s command-line tools and do this in a single line:

git add condor-example.py condor-example.sh condor-example.cmd

Or even:9

git add condor-example.*

That trio of files defines a batch program that reads two parameters on the command line: the mean of a gaussian, and the output file to which to write a histogram of that gaussian distribution.

Assume for the sake of the example that you want to add a third argument: the standard deviation of that gaussian. That requires making a coordinated change to all three files. As you worked on this, you could “bookmark” your work with:

git commit condor-example.py condor-example.sh condor-example.cmd -m "add a width argument"

Except that no one ever types something like that. They use the

following command; the -a means to commit changes to all the files

that git manages in this directory and any sub-directories:

git commit -a -m "add a width argument"

Simple version control

We’ve learned how to save versions of our files as we work on them. How do we make use of this feature?

There are a large number of possibilities. I’ll leave a description of most them to the Git book. Here’s a few commands to get you started:

# To look over all commits I made:

git log

# An abbreviated listing of the previous command.

# If you want to revert back to an earlier commit, this

# output is more convenient.

git reflog

# I've made changes, then realize that I don't like any of the work I

# did I can revert back to the files' as they were at the last commit:

git revert HEAD

# I want to revert back to a specific commit, perhaps just to look at

# it. Assume that 'git reflog' tells me that it's the commit with the

# ID 62ceb81.

git checkout 62ceb81

# If I want to make changes to this commit and make it the new starting

# point for my work:

git merge main

I’m a lying liar who lies

There’s a problem with all of the git examples above: I lied. For the

work that you’re likely to do with git, you won’t be using the git init command; you’ll do something more complex instead.

I’ll get to that in a subsequent page. But my conscience demands that I

admit my lie before you rush off to your home directory and type git init. You don’t want to do that.

Let me discuss a couple of other git-related topics first. Then I’ll get back to my lie.

- 1

What you’re actually doing is moving information from volatile memory to non-volatile storage. If you didn’t do this, you’d lose your work when your computer turns off.

- 2

Since I’m paranoid about losing my work, I save any file I’m working about once every sentence (or couple of lines of code, depending on what I’m writing). For example, I saved the file you’re reading now about once per footnote.

- 3

Since I prefer the keyboard version of the emacs text editor, actually I’m typing Ctrl-x Ctrl-s every few seconds.

- 4

For some reason this last item is on my mind as I type these words. I wonder why?

Figure 132: https://xkcd.com/1208/ by Randall Munroe

- 5

…at least in the way I’ve chosen to name the files. I’m sure you can think of a better scheme, at least for a single file.

- 6

If you follow some git guides, they’ll suggest to just use this command to initialize the repository:

git init

If you do this, the default name

masterwill be used for the main branch. Many in the software community are trying to get away from using names like “master” to describe coding relationships. I agree with those reasons, so I’m going to encourage the use of the wordmainin these instructions.- 7

If you’re interested in what the original files that I create look like, click on “View page source” in the upper right-hand corner of any of the pages in this tutorial. If you do, you’ll get an idea of how many files I updated as I added the topic of git to the tutorial.

- 8

No, I don’t expect you to read through the description of batch systems if that topic has no interest for you. It’s convenient for me to use these files because they have a clear relationship to a single purpose. You don’t have to know exactly what they do.

- 9

The advantage of having these be the only files in your git-managed directory is that you could do this:

git add .

This means to have git manage all the files in that directory.

I don’t like to use this form of the command. That’s because when I do my work, I usually create a bunch of temporary work files that I don’t want git to manage. I normally do a separate

git addfor each file I want git to control.