Repository

My lies are exposed

I’ll come clean: On the previous couple of pages, I presented the commands as if I was using git solely as a way of tracking my own files in my own project.

You can use git in this way.1 But that’s not the way you’re going to use it when you work with a scientific research group.

The truth is that you’re going to use git with a repository of some sort:

It may be that your files will be fairly independent with respect to others in your working group. In that case, you’ll probably be asked, at the end of the summer, to upload your files to a central git repository so that others can access what you’ve done.

It’s more likely that you’ll be asked to work with files that someone else has written. You’ll copy the files to your own area, and perhaps create one or more branches for your work. At some point, after testing and review, you might be asked to merge your work back into the original project.

The idea behind a git “repository” is that, in addition to maintaining the files in your own directory, there is some remote location (a different directory, a different computer, a different site) that also maintains a copy of the files.

When you’re working with git, files are only committed when you issue

a command (git commit). When you’re working with a repository, it

only receives an updated version of your committed files when you

issue a specific command (normally git push, which I’ll discuss

below).

Where will this remote location / repository be? It’s not hard to set up a git repository on any system.2

It’s more common these days to use a system that provides additional services above what what “vanilla” git offers. For the projects that I’ve worked on in physics, that system has been GitHub.3

As a practical matter, your working group will tell you which remote repository location to use. For the sake of simplicity, I’m going to assume that’s GitHub. For other services, your working group will provide directions.

Setup

The initial steps are:

Set up git. Note that git is already installed on every system of the Nevis particle-physics Linux cluster.

I find it’s easier to set up GitHub connections via SSH.4

Creating a new repository

Let’s assume that you’ve got your files in a directory. You’ve used git init to set up git to manage the files in that directory.5

You will want to define the remote repository using GitHub’s web interface.

The next step is to tell git that there’a remote repository associated with the contents of your local directory:

git remote add origin https://github.com/OWNER/REPOSITORY.git

Note that the name origin is can be any alias. However, the name

origin is standard and I suggest that you don’t change it.

To send the current git “state” (up to your most recent git commit)

to the remote repository, use git

push:

git push origin main

Note that this assumes that you used a couple of defaults:

originfor the alias for the remote repository;mainfor the default branch name.

Downloading an existing repository

As I noted above, this is the more likely case: Your working group has an established repository of files. They want you to copy this to your own area to work on it.

They’ll probably provide you with the necessary commands to do this. In case they haven’t, here are some generic instructions:

Clone the repository from GitHub. Assuming that you’ve set up an SSH key as I recommended above, the command will be something like:

git clone git@github.com:OWNER/REPOSITORY.git

This will create a directory in your area whose name is “REPOSITORY”. You do not create that directory in advance;

git clonewill create it for you.Note that the text

OWNERandREPOSITORYin the above command are examples. Your working group has to tell you the GitHub name of the owner of the repository, and the name of the repository.Go into that directory. Assuming that the directory has the naive name of

REPOSITORY:cd REPOSITORY

Bring the contents of that directory up-to-date with the remote repository, include all branches and tags:

git fetch

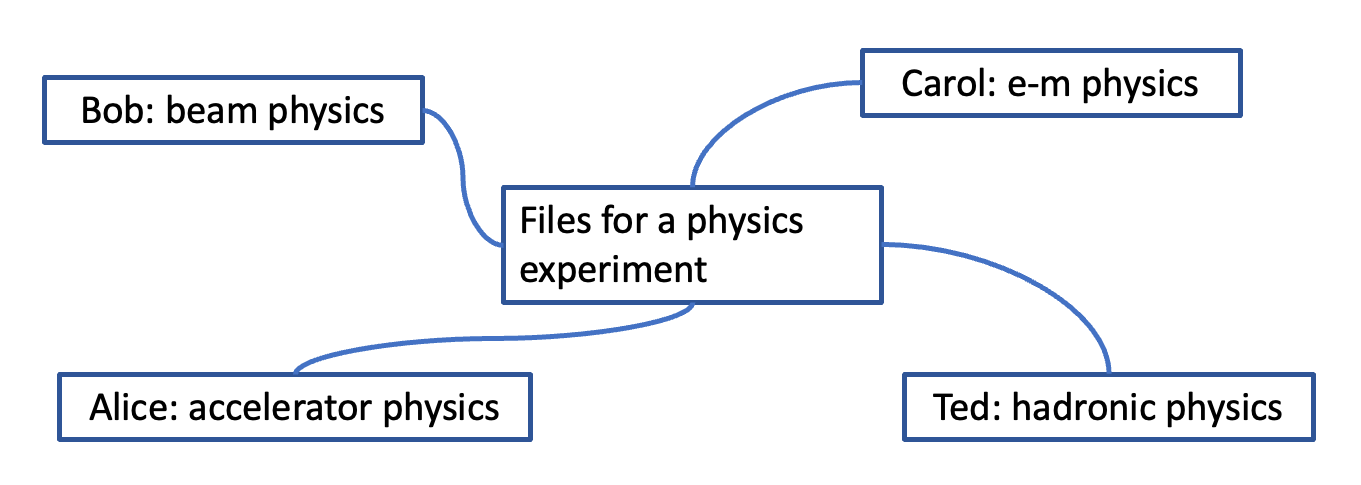

Figure 137: Here’s a sketch of what a physics software development environment might look like. A group of physicists are all working from the same code base. Perhaps they’re each creating their own branches as they work on their areas of expertise. At some point they’ll coordinate with each other (larger experiments have a software manager) to merge their work into the code in the central repository.

More fun with branches

Why would you want to use git fetch to synchronize all the branches

from the remote repository?

Many groups want you to make changes in a separate branch from the

main one. A common name for this branch is develop, but your working

group may have a different standard.

To switch to working with a branch named develop:

git checkout develop

You can simply work (and git commit) changes within that branch. You

can even create your own branch-within-a-branch if that turns out to

be practical for your work:

git commit -a -m "Save any commits I've made to the 'develop' branch"

git branch my_own_work

git checkout my_own_work

# Do whatever it is you'd like to do.

git commit -a -m "Commit the changes I made to 'my_own_work'"

# When it's ready and your working group approves:

git checkout develop

git merge my_own_work

If you’re going to push your work to the repository, make sure you’re pushing it to the correct remote branch; e.g.,

git push origin develop

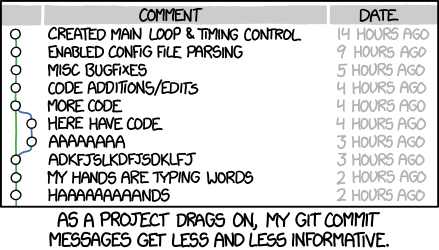

Figure 138: https://xkcd.com/1296/ by Randall Munroe

- 1

In fact, that’s how I use git to manage the files used to generate the web pages for this tutorial. As of 2025, I’ve not chosen to put the “source” code of these pages (what you see if you click “View page source” in the upper right) onto a central repository.

- 2

As proof of that statement, I’ve done it!

- 3

Editorial: My feelings on GitHub are decidedly mixed. On the one hand, GitHub is a free and convenient organizational tool for the kinds of projects that we see in the sciences. On the other hand, GitHub is owned by Microsoft, which almost certainly uses its content to train LLMs (remember my rant about LLMs?).

I’ve “shopped around” for a different well-known public repository service. As of 2025, I see Sourceforge and Gitlab as viable alternatives. However, any of these source-code hosting services are going to have some issue in my eyes, since they need to have some kind of revenue stream; that requirement doesn’t always agree with the development of scientific projects.

- 4

The reason why is that I already use tools like ssh-keygen to organize SSH keys between the computer systems I manage (and I encourage you to use it with your laptop-to-Nevis ssh connections). Adding my public SSH key to GitHub was trivial for me, since I already had a private key.

- 5

It’s not a bad practice to do this in an empty directory, then use git add to include files to manage as you work on them. Some guides suggest using a command like

git add .

This adds every file in your current directory to the list managed by git. However, I suggest not doing this.

The reason is that most of us create work files, intermediate edit files, and other miscellania that we don’t want to include in a formal project release. I think it’s better to add the specific files to track than to simply “add everything and sort it out later.”